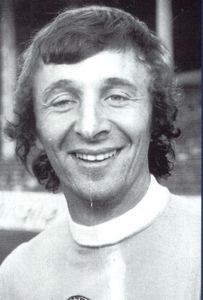

MIKE SUMMERBEE

The son of former Preston North End footballer George Summerbee, Mike Summerbee began his career with Bristol City but was released aged 15. He was signed by Swindon Town, making his debut aged 16 as a wet-behind-the ears winger. It was accepted that people in his position were of the, shall we say, ‘discerning nature’ when it came to physical contact and that’s how Mike began his career. For a few games, anyway. “I used to be a coward,” he said during an interview in May 1967, “but then I got the biggest telling off ever in front of the rest of the Swindon players and that changed me. “I had been playing centre forward for Swindon against Notts County and had pulled out of one or two tackles. After the match, Bert Head, the manager, really tore into me. All the players were there in the dressing room. I had never heard anything like it. I don’t think I have pulled out of a tackle since.”

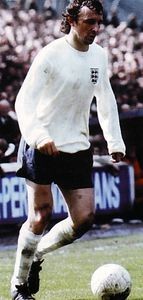

So the legend of the feisty forward was born and hundreds of bruised shins, yellow cards, early baths and suspensions later, the nickname ‘Buzzer’ was synonymous with fullbacks up and down the country who’d rather be somewhere else than face the slender No.7 with not so much fire in his belly as a raging inferno. Summerbee signed for City on August 20, 1965 at a cost of £35,000 and was one of Joe Mercer’s first signings.

He made his debut a day later in a 1-1 draw with Middlesbrough. Two days after his debut he was lucky not to have been killed in a car wreck, walking away with a few bruises. Fate had cleared another path for the youngster and he would play in all 52 league and cup games that season and though he failed to find the net in any of his first 21 matches for the Blues, he managed 10 in the remaining 31 as Mercer’s side clinched the Second Division title in style. Buzzer’s style quickly won approval from the City fans who enjoyed seeing their new star involved in a ruck with any of the gnarly old ffull-backs of the day. The defenders didn’t like it and he soon earned a reputation as someone who wasn’t afraid to mix it in the line of duty.

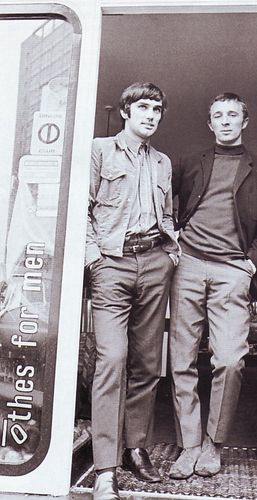

He became firm friends with City skipper Johnny Crossan and another lad from the sticks, Tony Book. Within a year of his arrival in Manchester, the West Country-raised lad had the lights of the bright city in his eyes and soon palled up with George Best and proceeded to paint the town red on a regular basis. The pair soon opened a boutique in the city centre, as fashion and designer clothes became a bigger part of his life.

He swapped his Volvo saloon for a blue Daimler Jag, complete with fur-covered seats and lived the life any young free and single bachelor would like to lead. His mantra on the pitch was hit them before they hit you and invariably he did just that, claiming that most full-backs didn’t wear shin pads as a rule – but they did when he was up against them.

City stumbled through the 1966/67 campaign and Buzzer’s influence was less than it should have been, but he felt the tactics weren’t necessarily maximising his game and he also believed he was worth a more lucrative contract. The end result was he asked for a transfer, though Joe Mercer told reporters “he’ll never leave this club while there’s still breath left in my body.”

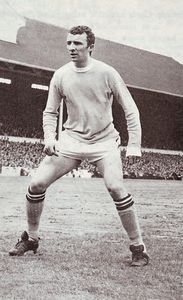

An impasse developed and it seemed Summerbee would quit Maine Road until a new deal was agreed and he returned for the 1967/68 campaign recharged and ready to go. Colin Bell was already at the club having signed the previous season but it wasn’t until Francis Lee arrived that City really began to motor.

Bell, Lee and Summerbee were the catalysts for the charge up Division One that would lead them to be nicknamed ‘The Holy Trinity’ and their input as the Blues snatched the league title away from Manchester United on the final day was immense. Summerbee won his first full England cap against Scotland in 1968 – the first City player to play for England in 12 years – having won recognition a year earlier for the England Under23s. But his final cap total would be the subject of much heated debate among City fans who felt he should have been a regular for the national side.

Referees were perhaps too quick to judge Summerbee as a troublemaker and he began to collect cards as though it were Christmas, leading to suspensions, FA hearings and all kinds of off-field shenanigans and fines. His reputation meant that on one occasion even an accidental collision resulted in a red card, though the alleged victim confirmed he wasn’t butted and helped clear his name at a hearing. For Buzzer, he knew it all went with the territory and accepted his punishments when given, though he stoically defended his name if there was a case of injustice. On his brushes with the other hard men of the era, he’d invariably give as good as he got and in one clash with Chelsea’s notorious hatchet man Ron ‘Chopper’ Harris, Buzzer felt his challenge, which had torn the back of Harris’ sock, was about to result in a right-hook from his opponent. “Hang on,” said Mike, “you’ve laddered your stocking.” You’ve either got it or you haven’t.

He was married in September 1968 but earned only two more England caps that year and City struggled again in the league, finishing 13th, but it was Buzzer’s persistence and perfectly-weighted cross for Neil Young that won the FA Cup against Leicester City in April 1969. Summerbee was loved by the City fans, particularly in derby matches where he and Mike Doyle would do all they could to wind up the Manchester United fans prior to the games. Once, Buzzer, prior to taking a corner, took the corner flag and pretended to blow his nose on it – in front of the Stretford End. He had bottle – plenty of it. He began the 1969 season in sparkling form and although their league display was average, City powered their way to Wembley in the League Cup and had reached the quarter-finals of the European Cup Winners’ Cup. Buzzer, however, was injured as City won the League Cup against West Brom with a suspected hairline fracture of the leg.

He battled back to help City to their first European final but his injury kept him out of the final and a decision to come back for a meaningless final day league fixture at Sheffield Wednesday proved costly as a knock on his leg caused a full break. Any hopes he’d harboured of travelling to the World Cup in Mexico vanished as he was ruled out for several months. He joined the club tour of Australia as no more than a guest and returned for the following season, which ended with a mid-table finish.

At least he won his fourth cap against Switzerland but his sporadic international career was a cause of frustration for him and his many admirers. He was back to his best again as City almost won the league championship again (see file marked Rodney Marsh) and won three more caps for his country in 1972. The disciplinary bans came and went and it was clear he’d lost none of his dander – he still enjoyed a laugh, too, and once threw snowballs during a wintry match at Maine Road. He also picked up the Player of the Year award in 1973.

Joe Mercer’s departure made little difference to his standing in the team but it was now an ageing side and it became a matter of who would be the first big name to leave the club.

Buzzer was made captain by new manager Ron Saunders in the 1973/74 season, won a final England cap and led City out at Wembley but, try as he did, he couldn’t inspire his team to a victory and Wolves won 2-1. Shortly after the final, champions elect Leeds United came in for him with a shock £75,000 bid to take him to Elland Road.

The deal fell through when Leeds backed out and a series of transfers collapsed with the failure to secure the cash, one of which was the Blues’ planned £175,000 purchase of promising Hull City striker Stuart Pearson (who would later become a legendary figure at Old Trafford). The move would have been a spectacular end to Buzzer’s days at the top and he must have felt hugely disappointed at missing out on the move at the time.

Off the pitch his shirt-making business was ticking along nicely (the boutique with Best now long gone) and Buzzer was by this time considering his future once he had hung up his boots.

Yet there was still plenty of life left in the old dog and the proud father of Rachel and son Nicky (who would later play for the Blues) was keen to have one last hurrah in his beloved sky blue jersey. Now in his 10th year at Maine Road, he made 26 appearances for City in 1974/75 but was transfer listed in January ’75 as it became clear his first-team opportunities would be limited under new boss Tony Book. Franny Lee had left the previous summer and the team was gradually being rebuilt. Manchester United, then in Division Two, had made an enquiry but did not follow their interest up and Buzzer remained at City until June when Burnley paid £25,000 to take him to Turf Moor, ending a decade of wonderful service.

He was awarded a testimonial in September 1975 and his old pal George Best even turned out for the Blues during an evening of entertaining football from some of the game’s best-loved stars. His post Maine Road career also included Blackpool and Stockport County, whom he was player-manager for a while before quitting in October 1979. He famously appeared in the 1981 movie Escape to Victory, alongside such luminaries as Pele and Sylvester Stallone where he played the role of British PoW Sid Harmer. He is, to this day, involved in the commercial department at City and has a regular column in the matchday programme and is still adored by the fans that were lucky enough to see him play at his peak. Committed, intelligent with a sense of humour drier than the Sahara Desert, Buzzer is one of the few footballers to have been sent off in a testimonial – that pretty much sums up this natural-born winner and a true City legend.

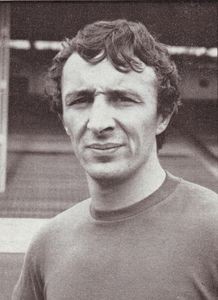

AN ARTICLE IN THE CITY MAGAZINE AUGUST 2006

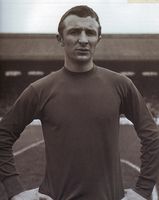

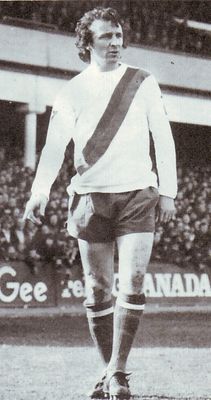

A TOPPS CARD FROM THE 1970S

AN INTERVIEW WITH MIKE SUMMERBEE FROM APRIL 2005

Let’s start with “Escape To Victory”. How did you get involved in the filming of that movie?

It was Bobby Moore who got me involved. We’d known each other since I was 16, and we both had a similar outlook. The makers of the film had got several Ipswich Town players involved, plus Pele and of course Bobby. They needed another familiar British Player and Bobby suggested me. He called me and said: “How do you fancy being in a movie with Michael Caine?” And that was it. Within three weeks I was on my way to Budapest for filming. l had no idea at the time that this would become one of those films still being shown and talked about twenty odd years later, but it has become a cult movie with websites dedicated to lt. It’s the sort of film that many other people would have wanted to be in. I know for a fact that Rod Stewart wanted to be in it.

Why do you think the film is remembered so affectionately?

l don‘t want to give too much away, everyone should come to our special showing and see the movie and hear my reasons then, but the film is like a Boys’ Own adventure. It’s got drama, excitement, and is a traditional film. lt doesn’t rely on bad language, sex, or extreme violence, and it really does appeal to everyone. Don’t forget it also contains some great actors, everyone remembers Stallone and Caine but look at the other cast members as well, and then there are some very well known footballers including Pele. I loved making the film and one of the great aspects for me was that when we came to the football scenes we were told to go out and play the game. John Huston, a great director, wanted it to look as realistic as possible and so we played a real game. Pele’s wonderful overhead kick goal was natural and was done only once. We didn’t take ages setting up. It was done for real and only in one take. John Huston had cameras everywhere and tried to make sure everything that took place on the pitch was filmed from every angle.

You have a speaking part in the film, did you know about that before you accepted?

We were told to let the actors act and they were told to let the footballers play. That way we all did what we were good at. Then when it came to the dressing room scenes Michael Caine said to Huston that it didn’t feel right for only the actors to talk and he said that a couple of us should speak. When it came to half time, I congratulated a couple of players on their play, that was natural not planned, and that stayed in, and then other lines were given to us. It felt strange, but when you watch the film it makes much more sense to have us speaking. I loved making the film and there are so many different aspects to talk about, but we’II save that for the 5th May event.

Moving back to your playing career, we all know that you came from a footballing family, but did that mean it was something you had to do?

My dad played professionally and so from an early age it seemed natural to play. All boys loved playing back then anyway, so there was nothing strange about that, but I suppose when you are young whatever your father does has a greater importance. My brother was a better player than I, although he stopped playing when my Dad died, and we used to play whenever and wherever we could. I’d get to school as early as possible — not for the ‘Iessons, I was a duncel — but for the kickabout. We’d have a tennis ball and play until we had to go in. I also played cricket, athletics and other sports, but football was my best.

Your progression into professional football seems rapid, you were a key feature of the Swindon team in your teens, were there any setbacks? I’d had a spell at Bristol City when I was 15, but I was so homesick I had to give up on it. My mother worried about me and suggested I kept out of the game. She knew about the problems and difficulties a footballer could have because of my father’s career, and then the opportunity came with Swindon and everything started going right for me. I joined them at a time when they were ready to give youth a chance and I made my debut at 17.

Was life relatively easy for you then?

The life of a footballer was not as glamorous or financially rewarding as it is today. I loved playing and I loved the camaraderie of it all, but we all had to have other jobs to keep us going outside of the season. I used to end up working for the Corporation cutting grass, painting, oddjobs, and digging graves! It kept you in touch with the fans, both the living and the dead! and I actually loved all of that time. We didn‘t have flash cars or anything then. Infact Ernie Hunt and I had a tandem, and we used to cycle together on our tandem to the ground. It was a great, fun time, and I have very fond memories of it all.

One of the significant angles is that Joe Mercer was interested in signing you from fairly early in your career, were you aware of his interest?

To some extent yes. Joe had played with my father at Aldershot, and then Swindon played Joe‘s Aston Villa in a testimonial game. We won and I scored a couple, and Joe even played wing-half for Villa. After that I was told he wanted to sign me for Villa and that he’d made a bid but nothing further happened. I don’t know if it was problems at Villa or what but some time after that Joe moved on, and then in 1965 he got the City job. I was in Torquay and I gave him a call, I thought it was time to make the move and chance my arm a little. Joe said he’d be in touch. Then serious interest came from City and I was off.

Did City mean much to you as a boy?

Because of where I lived I’d travel to Birmingham to watch games and whenever City played Villa I used to enjoy seeing Bobby Johnstone, Ken Barnes, Bert Trautmann and the rest. They were such a great and in many ways glamorous side to watch, and the pale blue shirt, a colour I still don‘t believe we’ve managed to recreate properly, was so memorable. No other side could match that colour and City were unique. All of those great memories were in my head and I was desperate to play for City when Joe came here. Although they were in Divsion Two when I arrived they were a major, major side with a great stadium. I loved Swindon, but City were something else.

Everyone talks about the atmosphere around the place, how did you find it?

Joe lifted the spirits of everybody, that was clear, and Malcolm Allison was so ahead of his time and knew all about psychology. He knew what players needed, and he always knew the best way of getting more out ot me was by winding me up. I think I was a consistent player, and at half time in one game we’d had a bit of a bad spell. I’d played well, but one or two players had struggled and we all knew it, but in the dressing room Mal went up to the two players and told them they were doing well and that they just had to keep plugging away. He was boosting their confidence I guess and they certainly were more confident in the second half. When he came to me he said I was playing the worst game ever and that I was letting everybody down! It wound me up so much I had a go back at him, and then when we got on the pitch I pushed and fought for everything to prove how wrong he was and I gave 120% – his trick had worked!

During your first year at City (1965-66) England manager Alf Ramsey came to watch you play, . and eventually you became the first City man since Don Revie in 1956 to play for England. Were you aware of the attention?

When Ramsey came to watch me the attention was good and considering Alf concentrated on his ‘wingless wondersl it was great for me a winger to be considered. I’d been included in the squad from almost immediately after the World Cup win, then I made my England debut against Scotland at Hampden (February 1968) in front of about 150,000, alongside the likes of Moore & Charlton. I was very nervous but they helped to calm me and at half time both Bobbys told me I was doing well, so that helped. In the end every one of my England appearances came at centre-forward, so I guess the style of play limited my opportunities, but I loved playing for England.

What was Alf Ramsey like as a manager? He was definitely a ‘player’s manager’. He handled us well, and I believe that he was, in the end, treated appallingly by the FA. He treated us exceptionally well and he was a great man to play for, I don’t believe England have ever managed to find a permanent manager who can match him. He had the same sort of authority as Joe Mercer, but they were different characters. Joe was wonderful with the media and the public, while Alf was primarily a players’ man. There was one time, we’d lost 2-0 at Katowice (1973) and I’d been on the bench. We were pretty down. Alf knew how low we were but because we were playing in Moscow a couple of days later he told everybody to get to bed early, no drinking or anything. We all sneaked into Bobby Moore’s room and had a few gins. Sir Alf caught us and we thought he was going to have a go. He said: “l thought I’d told you not to drink! But in the circumstances I’lI have a large gin and tonic please.”

Throughout the Sixties and Seventies, City never seemed to fear any opposition, is that something that came from the players?

Obviously, Joe and Malcolm bred a certain atmosphere which boosted confidence. Whenever we played United we’d get to Old Trafford at 12.30 simply to soak up the atmosphere and to be ready. Mal would swagger to the Stretford End before the game to tell them how many we’d win by, and we’d go out there and match his score, although we used to encourage him to keep the expectation down a little! For us it didn’t matter whether we played Shankly’s Liverpool, Busby’s United, or any other team because we knew we were more than a match for any of them. Some of these teams possessed better individual players, but, particularly at Old Trafford, we were always the better side. We had a great team spirit. People always , talk about Lee, Bell and Summerbee like Charlton, Law and Best, but our side wasn’t about three players, it was about the whole team. Oakes, Pardoe, Young. You know all the players. Unfortunately the trio was a good line for the media to focus on, but for the players it was always about the team.

Finally, you’ve always been known as an entertainer, and always had a great rapport with fans and the media, presumably this is a very important aspect to your life?

As a player I used to meet the fans as often as possible, we all would. We’d have lunch in the old Social Club all mixed together, we’d attend supporters & Junior Blues meetings; take part in the pantomime every year; and generally be out and about. We also used to get on well with the media. The journalists were always good honest judges back then, people like Frank McGhee and Richard Bott always talked truthfully about your performance. lf they said I’d had a bad game, I knew I had. They weren’t out to knock you, or to build you up. They spoke honestly and so I enjoyed talking with them. For me football is entertainment and the game itself is sometimes less important than everything that surrounds it. I don’t miss playing, but I do miss the camaraderie we had. I miss the team spirit we had with City, England, and. even during the filming of Escape To Victory. It’s the same camaraderie fans feel on the terraces. That’s why I enjoy my involvement with the Club today because it’s all about the fans, the City spirit, and the wonderful life that surrounds the game.

INTERVIEWED BY GARY JAMES AND PUBLISHED IN THE CITY PROGRAMME 9TH APRIL 2005